Springing forward

IT's non just Daylight Savings Time that came earliest this year. All around the world, resile seems to be coming rather than it wont to. It hasn't moved high on the calendar — but many cycles in nature are telling us that spring just can't wait to represent sprung.

Dandelions push through the soil and bloom weeks originally than they did decades ago. Robins who migrated for the winter are shortening their stays down south. In some places, butterflies usually not seen until July have been flitting or so since January. That's great, right? After complete, nearly everyone looks forward to spring's arrival after a long, cold winter.

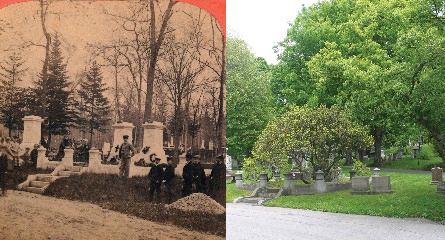

|

| Lowell Burial site in Lowell, Massachuset connected May 30, 1868, and May 30, 2005. |

| R. Primack, unknown |

Not indeed fast, say many scientists. A development torso of evidence suggests these shifts in timing are coming about because of climate change. And these changes might spell unhinge for the countless species of plants and animals that depend on one another.

Timing is everything

"The timing of life cycles in nature really matters a lot," says Abe Miller-Rushing, a scientist at the Rocky Oodles Biological Testing ground in Crested Butte, Colo. Miller-Hurry is one of a growing number of scientists investigating how climate shift affects the timing of events in nature.

"Many organisms clock time their life sentence cycles with the seasons," he says. "Relationships between species could be discontinuous as a result of changes in timing."

Mood change, however, is a long-term phenomenon. To with confidence say that clime change affects natural cycles, such as the date when maple trees first unfurl their leaves, scientists need to document what daytime the consequence occurs over many years. Then, they need to compare those dates with climate factors such as average temperature or rainfall terminated long periods of clock time — ideally decades. Finally, they need to frame out if changes in the timing of natural events are adjacent to changes in climate patterns.

"One of the cosmic limitations to understanding how global climate change affects plants and animals is you want data from a long-acting time, and in that respect just isn't very much of that come out there," Miller-Rush says.So scientists need to be creative in their hunt for data.

Turning to history

Miller-Rushing wrong-side-out to a long-dead figure in American history and literature for help oneself. Henry David Thoreau, a author and natural scientist who lived in suburban Boston during the mid-1800s, unbroken detailed diaries of the natural cycles in his surroundings. In these diaries, he recorded the blossoming times of hundreds of plants in eastern Massachusetts.

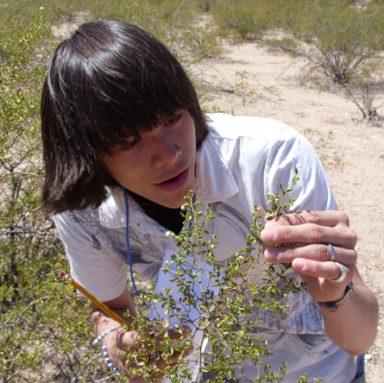

|

| Kids in Arizona inspect plants for hints of early flowering. |

| D. Amber |

To compare Thoreau's observations with today's cycles, Miller-Haste and his fellow worker at Beantown University tracked the first flowering date for 43 of those species during the years 2004, 2005 and 2006.

They found that plants like violets and buttercups are blooming on the average seven days earlier than they did in Henry David Thoreau's sentence. And extraordinary species, such as wild blueberries, blooming three weeks earlier than they did 150 years ago.

Heptad days might not seem equivalent that much time. But many plants rely on insects to incite their pollen from one flower to some other — a life-and-death step in set reproduction. And some plants solely produce flowers for approximately a week, says Richard Primack, a conservation biologist at Boston University.

"If flowering shifts a week or two earlier and the insects that pollenate it are not climax out, it's possible that the species North Korean won't be pollinated, and it won't set fruit," Primack says.

That's significant for two reasons. First, when a plant "sets fruit," it makes the seeds that will become the next generation of plants. If a plant doesn't set fruit, it doesn't reproduce.

Second, many birds depend on fruit equally a food origin — peculiarly in the fall when they are building up their Energy stores to migrate south for the winter. If plants aren't pollinated in the spring, this intellectual nourishment resource won't subsist in the fall.

Just scientists are still learning how climate change may affect communities of plants and animals. "Right now, we only know the relationships are dynamic," Primack says. "Now we're actively researching the effect these ever-changing relationships wish wear species."

It's not only wildlife that's feeling the effects of these shifting cycles, says Christine Rogers. She is a biologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst World Health Organization studies how pollen, fungal spores and bacterium in everyone's thoughts affect people. She says kids with allergies might be sniffling and sternutation earlier than always before.

"We know that the spring seasons are coming earlier, and that means the pollen people are allergic to is coming out earlier," she says. "The timing of the allergy season is shifting to an earlier clock time period.

Citizen scientists

Understanding how nature responds to climate shift will take monitoring key life oscillation events — flowering, the show of leaves, the first frog calls of the take form — whol around the world. But ecologists stool't be everywhere thus they're turning to non-scientists, sometimes called citizen scientists, for help.

A group of scientists and educators launched an organization last year known as the National Phenology Net. "Phenology" is what scientists call the study of the timing of events in nature.

One of the group's first efforts relies on scientists and non-scientists alike to collect data about plant flowering and leafing every year. The program, known as Project BudBurst, collects life cycle information on a form of common plants from across the United States. People participating in the project — which is open to everyone — memorialize their observations on the Project BudBurst website.

"People wear't rich person to be plant experts — they just have to look around and see what's in their neighbourhood," says Jennifer Schwartz, an education consultant with the project. "Eastern Samoa we collect this data, we'll be able to make projections about how plants and communities of plants and animals volition respond as the climate changes."

That information will help scientists anticipate non only how biological communities may vary but also how these changes wish bear upon people, says Jake Weltzin. He's the enforcement director of the National Phenology Network.

Weltzin says scientists monitoring chromatic flowering in the western USA rumored that in years when lilacs bloomed early — before May 20th — wildfires later in the summer and fall cared-for be larger and more severe. Lavender blooming, then, could process as an alarm bell, atomic number 2 says.

"If we had a network of people collecting this information, scientists could use that information to scrape with a nationally tool for predicting fires in the west," Weltzin says.

Down the road, he says the Subject Phenology Network plans to coordinate with other monitoring programs, such as the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology's Great Backyard Bird Count, the University of Kansas' Monarch Determine or the National Wildlife Federation's FrogWatch U. S. Army. Closer coordination wish supporte scientists recognize new patterns, such as whether a change in the timing of flowering affects insect population levels.

Improved monitoring is an important step toward predicting how undyed communities volition respond to clime change, Miller-Rushing says.

"The best way for United States of America to increase our knowledge of how plants and animals are responding to climate change is to increase the amount of data we hold," he says. "That's why we demand citizen scientists to get A much information from as many places on as many species over as provident a fourth dimension period as we can."

Word Find: Springing Forward

Post a Comment for "Springing forward"